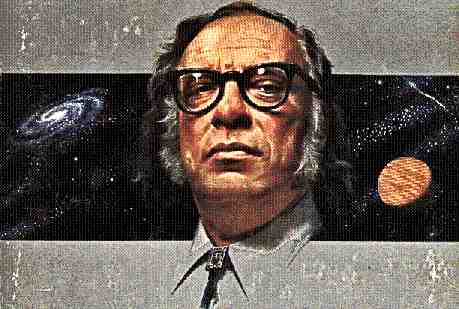

One of my favorite authors of all time, Isaac Asimov, is an American best known for his works of science fiction. Some years ago, I stumbled upon his two short stories “The Last Question” and “The Last Answer”. The first one being Asimov’s favorite short story written by himself. But they are both good stories, and it’s for me, difficult to point out which one is better. I highly suggest reading them both, but I’m not sure what order to recommend. Read both stories before looking at the comments on either one, because they are filled with spoilers.

So without further ado:

The Last Answer by Isaac Asimov — © 1980

Murray Templeton was forty-five years old, in the prime of life, and with all parts of his body in perfect working order except for certain key portions of his coronary arteries, but that was enough.

The pain had come suddenly, had mounted to an unbearable peak, and had then ebbed steadily. He could feel his breath slowing and a kind of gathering peace washing over him.

There is no pleasure like the absence of pain – immediately after pain. Murray felt an almost giddy lightness as though he were lifting in the air and hovering.

He opened his eyes and noted with distant amusement that the others in the room were still agitated. He had been in the laboratory when the pain had struck, quite without warning, and when he had staggered, he had heard surprised outcries from the others before everything vanished into overwhelming agony.

Now, with the pain gone, the others were still hovering, still anxious, still gathered about his fallen body –– Which, he suddenly realised, he was looking down on.

He was down there, sprawled, face contorted. He was up here, at peace and watching.

He thought: Miracle of miracles! The life-after-life nuts were right.

And although that was a humiliating way for an atheistic physicist to die, he felt only the mildest surprise, and no alteration of the peace in which he was immersed.

He thought: There should be some angel – or something – coming for me.

The Earthly scene was fading. Darkness was invading his consciousness and off in a distance, as a last glimmer of sight, there was a figure of light, vaguely human in form, and radiating warmth.

Murray thought: What a joke on me. I’m going to Heaven.

Even as he thought that, the light faded, but the warmth remained. There was no lessening of the peace even though in all the Universe only he remained – and the Voice.

The Voice said, “I have done this so often and yet I still have the capacity to be pleased at success.”

It was in Murray’s mind to say something, but he was not conscious of possessing a mouth, tongue, or vocal chords. Nevertheless, tried to make a sound. He tried, mouthlessly, to hum words or breathe them or just push them out by a contraction of – something.

And they came out. He heard his own voice, quite recognisable, and his own words, infinitely clear.

Murray said, “Is this Heaven?”

The Voice said, “This is no place as you understand place.”

Murray was embarrassed, but the next question had to be asked. “Pardon me if I sound like a jackass. Are you God?”

Without changing intonation or in any way marring the perfection of the sound, the Voice managed to sound amused. “It is strange that I am always asked that in, of course, an infinite number of ways. There is no answer I can give that you would comprehend. I am – which is all that I can say significantly and you may cover that with any word or concept you please.”

Murray said, “And what am I? A soul? Or am I only personified existence too?” He tried not to sound sarcastic, but it seemed to him that he had failed. He thought then, fleetingly, of adding a ‘Your Grace’ or ‘Holy One’ or something to counteract the sarcasm, and could not bring himself to do so even though for the first time in his existence he speculated on the possibility of being punished for his insolence – or sin? – with Hell, and what that might be like.

The Voice did not sound offended. “You are easy to explain – even to you. You may call yourself a soul if that pleases you, but what you are is a nexus of electromagnetic forces, so arranged that all the interconnections and interrelationships are exactly imitative of those of your brain in your Universe-existence – down to the smallest detail. Therefore you have your capacity for thought, your memories, your personality. It still seems to you that you are you.”

Murray found himself incredulous. “You mean the essence of my brain was permanent?”

“Not at all. There is nothing about you that is permanent except what I choose to make so. I formed the nexus. I constructed it while you had physical existence and adjusted it to the moment when the existence failed.”

The Voice seemed distinctly pleased with itself, and went on after a moment’s pause. “An intricate but entirely precise construction. I could, of course, do it for every human being on your world but I am pleased that I do not. There is pleasure in the selection.”

“You choose very few then?”

“Very few.”

“And what happens to the rest?”

“Oblivion! – Oh, of course, you imagine a Hell.”

Murray would have flushed if he had the capacity to do so. He said, “I do not. It is spoken of. Still, I would scarcely have thought I was virtuous enough to have attracted your attention as one of the Elect.”

“Virtuous? – Ah, I see what you mean. It is troublesome to have to force my thinking small enough to permeate yours. No, I have chosen you for your capacity for thought, as I choose others, in quadrillions, from all the intelligent species of the Universe.”

Murray found himself suddenly curious, the habit of a lifetime. He said, “Do you choose them all yourself or are there others like you?”

For a fleeting moment, Murray thought there was an impatient reaction to that, but when the Voice came, it was unmoved. “Whether or not there are others is irrelevant to you. This Universe is mine, and mine alone. It is my invention, my construction, intended for my purpose alone.”

“And yet with quadrillions of nexi you have formed, you spend time with me? Am I that important?”

The Voice said, “You are not important at all. I am also with others in a way which, to your perception, would seem simultaneous.”

“And yet you are one?”

Again amusement. The Voice said, “You seek to trap me into an inconsistency. If you were an amoeba who could consider individuality only in connection with single cells and if you were to ask a sperm whale, made up of thirty quadrillion cells, whether it was one or many, how could the sperm whale answer in a way that would be comprehensible to the amoeba?”

Murray said dryly, “I’ll think about it. It may become comprehensible.”

“Exactly. That is your function. You will think.”

“To what end? You already know everything, I suppose.”

The Voice said, “Even if I knew everything, I could not know that I know everything.”

Murray said, “That sounds like a bit of Eastern philosophy – something that sounds profound precisely because it has no meaning.”

The Voice said, “You have promise. You answer my paradox with a paradox – except that mine is not a paradox. Consider. I have existed eternally, but what does that mean? It means I cannot remember having come into existence. If I could, I would not have existed eternally. If I cannot remember having come into existence, then there is at least one thing – the nature of my coming into existence – that I do not know.

“Then, too, although what I know is infinite, it is also true that what there is to know is infinite, and how can I be sure that both infinities are equal? The infinity of potential knowledge may be infinitely greater than the infinity of my actual knowledge. Here is a simple example: If I knew every one of the even integers, I would know an infinite number of items, and yet I would still not know a single odd integer.”

Murray said, “But the odd integers can be derived. If you divide every even integer in the entire infinite series by two, you will get another infinite series which will contain within it the infinite series of odd integers.”

The Voice said, “You have the idea. I am pleased. It will be your task to find other such ways, far more difficult ones, from the known to the not-yet-known. You have your memories. You will remember all the data you have ever collected or learned, or that you have or will deduce from that data. If necessary, you will be allowed to learn what additional data you will consider relevant to the problems you set yourself.”

“Could you not do all that for yourself?”

The Voice said, “I can, but it is more interesting this way. I constructed the Universe in order to have more facts to deal with. I inserted the uncertainty principle, entropy, and other randomisation factors to make the whole not instantly obvious. It has worked well for it has amused me throughout its entire existence.

“I then allowed complexities that produced first life and then intelligence, and use it as a source for a research team, not because I need the aid, but because it would introduce a new random factor. I found I could not predict the next interesting piece of knowledge gained, where it would come from, by what means derived.”

Murray said, “Does that ever happen?”

“Certainly. A century doesn’t pass in which some interesting item doesn’t appear somewhere.”

“Something that you could have thought of yourself, but had not done so yet?”

“Yes.”

Murray said, “Do you actually think there’s a chance of my obliging you in this manner?”

“In the next century? Virtually none. In the long run, though, your success is certain, since you will be engaged eternally.”

Murray said, “I will be thinking through eternity? Forever?”

“Yes.”

“To what end?”

“I have told you. To find new knowledge.”

“But beyond that. For what purpose am I to find new knowledge?”

“It was what you did in your Universe-bound life. What was its purpose then?”

Murray said, “To gain new knowledge that only I could gain. To receive the praise of my fellows. To feel the satisfaction of accomplishment knowing that I had only a short time allotted me for the purpose. – Now I would gain only what you could gain yourself if you wished to take a small bit of trouble. You cannot praise me; you can only be amused. And there is no credit or satisfaction in accomplishment when I have all eternity to do it in.”

The Voice said, “And you do not find thought and discovery worthwhile in itself? You do not find it requiring no further purpose?”

“For a finite time, yes. Not for all eternity.”

“I see your point. Nevertheless, you have no choice.”

“You say I am to think. You cannot make me do so.”

The Voice said, “I do not wish to constrain you directly. I will not need to. Since you can do nothing but think, you will think. You do not know how not to think.”

“Then I will give myself a goal. I will invent a purpose.”

The Voice said tolerantly, “That you can certainly do.”

“I have already found a purpose.”

“May I know what it is?”

“You know already. I know we are not speaking in the ordinary fashion. You adjust my nexus is such a way that I believe I hear you and I believe I speak, but you transfer thoughts to me and from me directly. And when my nexus changes with my thoughts you are at once aware of them and do not need my voluntary transmission.”

The Voice said, “You are surprisingly correct. I am pleased. – But it also pleases me to have you tell me your thoughts voluntarily.”

“Then I will tell you. The purpose of my thinking will be to discover a way to disrupt this nexus of me that you have created. I do not want to think for no purpose but to amuse you. I do not want to think forever to amuse you. I do not want to exist forever to amuse you. All my thinking will be directed toward ending the nexus. That would amuse me.”

The Voice said, “I have no objection to that. Even concentrated thought on ending your own existence may, in spite of you, come up with something new and interesting. And, of course, if you succeed in this suicide attempt you will have accomplished nothing, for I would instantly reconstruct you and in such a way as to make your method of suicide impossible. And if you found another and still more subtle fashion of disrupting yourself, I would reconstruct you with that possibility eliminated, and so on. It could be an interesting game, but you will nevertheless exist eternally. It is my will.”

Murray felt a quaver but the words came out with a perfect calm. “Am I in Hell then, after all? You have implied there is none, but if this were Hell you would lie to us as part of the game of Hell.”

The Voice said, “In that case, of what use is it to assure you that you are not in Hell? Nevertheless, I assure you. There is here neither Heaven nor Hell. There is only myself.”

Murray said, “Consider, then, that my thoughts may be useless to you. If I come up with nothing useful, will it not be worth your while to – disassemble me and take no further trouble with me?”

“As a reward? You want Nirvana as the prize of failure and you intend to assure me failure? There is no bargain there. You will not fail. With all eternity before you, you cannot avoid having at least one interesting thought, however you try against it.”

“Then I will create another purpose for myself. I will not try to destroy myself. I will set as my goal the humiliation of you. I will think of something you have not only never thought of but never could think of. I will think of the last answer, beyond which there is no knowledge further.”

The Voice said, “You do not understand the nature of the infinite. There may be things I have not yet troubled to know. There cannot be anything I cannot know.”

Murray said thoughtfully, “You cannot know your beginning. You have said so. Therefore you cannot know your end. Very well, then. That will be my purpose and that will be the last answer. I will not destroy myself. I will destroy you – if you do not destroy me first.”

The Voice said, “Ah! You come to that in rather less than average time. I would have thought it would have taken you longer. There is not one of those I have with me in this existence of perfect and eternal thought that does not have the ambition of destroying me. It cannot be done.”

Murray said, “I have all eternity to think of a way of destroying you.”

The Voice said, equably, “Then try to think of it.” And it was gone.

But Murray had his purpose now and was content.

For what could any Entity, conscious of eternal existence, want – but an end?

For what else had the Voice been searching for countless billions of years? And for what other reason had intelligence been created and certain specimens salvaged and put to work, but to aid in that great search? And Murray intended that it would be he, and he alone, who would succeed.

Carefully, and with the thrill of purpose, Murray began to think.

He had plenty of time.

And his personal favorite:

The Last Question by Isaac Asimov — © 1956

The last question was asked for the first time, half in jest, on May 21, 2061, at a time when humanity first stepped into the light. The question came about as a result of a five dollar bet over highballs, and it happened this way:

Alexander Adell and Bertram Lupov were two of the faithful attendants of Multivac. As well as any human beings could, they knew what lay behind the cold, clicking, flashing face — miles and miles of face — of that giant computer. They had at least a vague notion of the general plan of relays and circuits that had long since grown past the point where any single human could possibly have a firm grasp of the whole.

Multivac was self-adjusting and self-correcting. It had to be, for nothing human could adjust and correct it quickly enough or even adequately enough — so Adell and Lupov attended the monstrous giant only lightly and superficially, yet as well as any men could. They fed it data, adjusted questions to its needs and translated the answers that were issued. Certainly they, and all others like them, were fully entitled to share In the glory that was Multivac’s.

For decades, Multivac had helped design the ships and plot the trajectories that enabled man to reach the Moon, Mars, and Venus, but past that, Earth’s poor resources could not support the ships. Too much energy was needed for the long trips. Earth exploited its coal and uranium with increasing efficiency, but there was only so much of both.

But slowly Multivac learned enough to answer deeper questions more fundamentally, and on May 14, 2061, what had been theory, became fact.

The energy of the sun was stored, converted, and utilized directly on a planet-wide scale. All Earth turned off its burning coal, its fissioning uranium, and flipped the switch that connected all of it to a small station, one mile in diameter, circling the Earth at half the distance of the Moon. All Earth ran by invisible beams of sunpower.

Seven days had not sufficed to dim the glory of it and Adell and Lupov finally managed to escape from the public function, and to meet in quiet where no one would think of looking for them, in the deserted underground chambers, where portions of the mighty buried body of Multivac showed. Unattended, idling, sorting data with contented lazy clickings, Multivac, too, had earned its vacation and the boys appreciated that. They had no intention, originally, of disturbing it.

They had brought a bottle with them, and their only concern at the moment was to relax in the company of each other and the bottle.

«It’s amazing when you think of it,» said Adell. His broad face had lines of weariness in it, and he stirred his drink slowly with a glass rod, watching the cubes of ice slur clumsily about. «All the energy we can possibly ever use for free. Enough energy, if we wanted to draw on it, to melt all Earth into a big drop of impure liquid iron, and still never miss the energy so used. All the energy we could ever use, forever and forever and forever.»

Lupov cocked his head sideways. He had a trick of doing that when he wanted to be contrary, and he wanted to be contrary now, partly because he had had to carry the ice and glassware. «Not forever,» he said.

«Oh, hell, just about forever. Till the sun runs down, Bert.»

«That’s not forever.»

«All right, then. Billions and billions of years. Twenty billion, maybe. Are you satisfied?»

Lupov put his fingers through his thinning hair as though to reassure himself that some was still left and sipped gently at his own drink. «Twenty billion years isn’t forever.»

«Will, it will last our time, won’t it?»

«So would the coal and uranium.»

«All right, but now we can hook up each individual spaceship to the Solar Station, and it can go to Pluto and back a million times without ever worrying about fuel. You can’t do THAT on coal and uranium. Ask Multivac, if you don’t believe me.»

«I don’t have to ask Multivac. I know that.»

«Then stop running down what Multivac’s done for us,» said Adell, blazing up. «It did all right.»

«Who says it didn’t? What I say is that a sun won’t last forever. That’s all I’m saying. We’re safe for twenty billion years, but then what?» Lupov pointed a slightly shaky finger at the other. «And don’t say we’ll switch to another sun.»

There was silence for a while. Adell put his glass to his lips only occasionally, and Lupov’s eyes slowly closed. They rested.

Then Lupov’s eyes snapped open. «You’re thinking we’ll switch to another sun when ours is done, aren’t you?»

«I’m not thinking.»

«Sure you are. You’re weak on logic, that’s the trouble with you. You’re like the guy in the story who was caught in a sudden shower and Who ran to a grove of trees and got under one. He wasn’t worried, you see, because he figured when one tree got wet through, he would just get under another one.»

«I get it,» said Adell. «Don’t shout. When the sun is done, the other stars will be gone, too.»

«Darn right they will,» muttered Lupov. «It all had a beginning in the original cosmic explosion, whatever that was, and it’ll all have an end when all the stars run down. Some run down faster than others. Hell, the giants won’t last a hundred million years. The sun will last twenty billion years and maybe the dwarfs will last a hundred billion for all the good they are. But just give us a trillion years and everything will be dark. Entropy has to increase to maximum, that’s all.»

«I know all about entropy,» said Adell, standing on his dignity.

«The hell you do.»

«I know as much as you do.»

«Then you know everything’s got to run down someday.»

«All right. Who says they won’t?»

«You did, you poor sap. You said we had all the energy we needed, forever. You said ‘forever.'»

«It was Adell’s turn to be contrary. «Maybe we can build things up again someday,» he said.

«Never.»

«Why not? Someday.»

«Never.»

«Ask Multivac.»

«You ask Multivac. I dare you. Five dollars says it can’t be done.»

Adell was just drunk enough to try, just sober enough to be able to phrase the necessary symbols and operations into a question which, in words, might have corresponded to this: Will mankind one day without the net expenditure of energy be able to restore the sun to its full youthfulness even after it had died of old age?

Or maybe it could be put more simply like this: How can the net amount of entropy of the universe be massively decreased?

Multivac fell dead and silent. The slow flashing of lights ceased, the distant sounds of clicking relays ended.

Then, just as the frightened technicians felt they could hold their breath no longer, there was a sudden springing to life of the teletype attached to that portion of Multivac. Five words were printed: INSUFFICIENT DATA FOR MEANINGFUL ANSWER.

«No bet,» whispered Lupov. They left hurriedly.

By next morning, the two, plagued with throbbing head and cottony mouth, had forgotten about the incident.

Jerrodd, Jerrodine, and Jerrodette I and II watched the starry picture in the visiplate change as the passage through hyperspace was completed in its non-time lapse. At once, the even powdering of stars gave way to the predominance of a single bright marble-disk, centered.

«That’s X-23,» said Jerrodd confidently. His thin hands clamped tightly behind his back and the knuckles whitened.

The little Jerrodettes, both girls, had experienced the hyperspace passage for the first time in their lives and were self-conscious over the momentary sensation of inside-outness. They buried their giggles and chased one another wildly about their mother, screaming, «We’ve reached X-23 — we’ve reached X-23 — we’ve —-»

«Quiet, children,» said Jerrodine sharply. «Are you sure, Jerrodd?»

«What is there to be but sure?» asked Jerrodd, glancing up at the bulge of featureless metal just under the ceiling. It ran the length of the room, disappearing through the wall at either end. It was as long as the ship.

Jerrodd scarcely knew a thing about the thick rod of metal except that it was called a Microvac, that one asked it questions if one wished; that if one did not it still had its task of guiding the ship to a preordered destination; of feeding on energies from the various Sub-galactic Power Stations; of computing the equations for the hyperspacial jumps.

Jerrodd and his family had only to wait and live in the comfortable residence quarters of the ship.

Someone had once told Jerrodd that the «ac» at the end of «Microvac» stood for «analog computer» in ancient English, but he was on the edge of forgetting even that.

Jerrodine’s eyes were moist as she watched the visiplate. «I can’t help it. I feel funny about leaving Earth.»

«Why for Pete’s sake?» demanded Jerrodd. «We had nothing there. We’ll have everything on X-23. You won’t be alone. You won’t be a pioneer. There are over a million people on the planet already. Good Lord, our great grandchildren will be looking for new worlds because X-23 will be overcrowded.»

Then, after a reflective pause, «I tell you, it’s a lucky thing the computers worked out interstellar travel the way the race is growing.»

«I know, I know,» said Jerrodine miserably.

Jerrodette I said promptly, «Our Microvac is the best Microvac in the world.»

«I think so, too,» said Jerrodd, tousling her hair.

It was a nice feeling to have a Microvac of your own and Jerrodd was glad he was part of his generation and no other. In his father’s youth, the only computers had been tremendous machines taking up a hundred square miles of land. There was only one to a planet. Planetary ACs they were called. They had been growing in size steadily for a thousand years and then, all at once, came refinement. In place of transistors had come molecular valves so that even the largest Planetary AC could be put into a space only half the volume of a spaceship.

Jerrodd felt uplifted, as he always did when he thought that his own personal Microvac was many times more complicated than the ancient and primitive Multivac that had first tamed the Sun, and almost as complicated as Earth’s Planetary AC (the largest) that had first solved the problem of hyperspatial travel and had made trips to the stars possible.

«So many stars, so many planets,» sighed Jerrodine, busy with her own thoughts. «I suppose families will be going out to new planets forever, the way we are now.»

«Not forever,» said Jerrodd, with a smile. «It will all stop someday, but not for billions of years. Many billions. Even the stars run down, you know. Entropy must increase.»

«What’s entropy, daddy?» shrilled Jerrodette II.

«Entropy, little sweet, is just a word which means the amount of running-down of the universe. Everything runs down, you know, like your little walkie-talkie robot, remember?»

«Can’t you just put in a new power-unit, like with my robot?»

The stars are the power-units, dear. Once they’re gone, there are no more power-units.»

Jerrodette I at once set up a howl. «Don’t let them, daddy. Don’t let the stars run down.»

«Now look what you’ve done, » whispered Jerrodine, exasperated.

«How was I to know it would frighten them?» Jerrodd whispered back.

«Ask the Microvac,» wailed Jerrodette I. «Ask him how to turn the stars on again.»

«Go ahead,» said Jerrodine. «It will quiet them down.» (Jerrodette II was beginning to cry, also.)

Jarrodd shrugged. «Now, now, honeys. I’ll ask Microvac. Don’t worry, he’ll tell us.»

He asked the Microvac, adding quickly, «Print the answer.»

Jerrodd cupped the strip of thin cellufilm and said cheerfully, «See now, the Microvac says it will take care of everything when the time comes so don’t worry.»

Jerrodine said, «and now children, it’s time for bed. We’ll be in our new home soon.»

Jerrodd read the words on the cellufilm again before destroying it: INSUFFICIENT DATA FOR A MEANINGFUL ANSWER.

He shrugged and looked at the visiplate. X-23 was just ahead.

VJ-23X of Lameth stared into the black depths of the three-dimensional, small-scale map of the Galaxy and said, «Are we ridiculous, I wonder, in being so concerned about the matter?»

MQ-17J of Nicron shook his head. «I think not. You know the Galaxy will be filled in five years at the present rate of expansion.»

Both seemed in their early twenties, both were tall and perfectly formed.

«Still,» said VJ-23X, «I hesitate to submit a pessimistic report to the Galactic Council.»

«I wouldn’t consider any other kind of report. Stir them up a bit. We’ve got to stir them up.»

VJ-23X sighed. «Space is infinite. A hundred billion Galaxies are there for the taking. More.»

«A hundred billion is not infinite and it’s getting less infinite all the time. Consider! Twenty thousand years ago, mankind first solved the problem of utilizing stellar energy, and a few centuries later, interstellar travel became possible. It took mankind a million years to fill one small world and then only fifteen thousand years to fill the rest of the Galaxy. Now the population doubles every ten years –»

VJ-23X interrupted. «We can thank immortality for that.»

«Very well. Immortality exists and we have to take it into account. I admit it has its seamy side, this immortality. The Galactic AC has solved many problems for us, but in solving the problems of preventing old age and death, it has undone all its other solutions.»

«Yet you wouldn’t want to abandon life, I suppose.»

«Not at all,» snapped MQ-17J, softening it at once to, «Not yet. I’m by no means old enough. How old are you?»

«Two hundred twenty-three. And you?»

«I’m still under two hundred. –But to get back to my point. Population doubles every ten years. Once this Galaxy is filled, we’ll have another filled in ten years. Another ten years and we’ll have filled two more. Another decade, four more. In a hundred years, we’ll have filled a thousand Galaxies. In a thousand years, a million Galaxies. In ten thousand years, the entire known Universe. Then what?»

VJ-23X said, «As a side issue, there’s a problem of transportation. I wonder how many sunpower units it will take to move Galaxies of individuals from one Galaxy to the next.»

«A very good point. Already, mankind consumes two sunpower units per year.»

«Most of it’s wasted. After all, our own Galaxy alone pours out a thousand sunpower units a year and we only use two of those.»

«Granted, but even with a hundred per cent efficiency, we can only stave off the end. Our energy requirements are going up in geometric progression even faster than our population. We’ll run out of energy even sooner than we run out of Galaxies. A good point. A very good point.»

«We’ll just have to build new stars out of interstellar gas.»

«Or out of dissipated heat?» asked MQ-17J, sarcastically.

«There may be some way to reverse entropy. We ought to ask the Galactic AC.»

VJ-23X was not really serious, but MQ-17J pulled out his AC-contact from his pocket and placed it on the table before him.

«I’ve half a mind to,» he said. «It’s something the human race will have to face someday.»

He stared somberly at his small AC-contact. It was only two inches cubed and nothing in itself, but it was connected through hyperspace with the great Galactic AC that served all mankind. Hyperspace considered, it was an integral part of the Galactic AC.

MQ-17J paused to wonder if someday in his immortal life he would get to see the Galactic AC. It was on a little world of its own, a spider webbing of force-beams holding the matter within which surges of sub-mesons took the place of the old clumsy molecular valves. Yet despite it’s sub-etheric workings, the Galactic AC was known to be a full thousand feet across.

MQ-17J asked suddenly of his AC-contact, «Can entropy ever be reversed?»

VJ-23X looked startled and said at once, «Oh, say, I didn’t really mean to have you ask that.»

«Why not?»

«We both know entropy can’t be reversed. You can’t turn smoke and ash back into a tree.»

«Do you have trees on your world?» asked MQ-17J.

The sound of the Galactic AC startled them into silence. Its voice came thin and beautiful out of the small AC-contact on the desk. It said: THERE IS INSUFFICIENT DATA FOR A MEANINGFUL ANSWER.

VJ-23X said, «See!»

The two men thereupon returned to the question of the report they were to make to the Galactic Council.

Zee Prime’s mind spanned the new Galaxy with a faint interest in the countless twists of stars that powdered it. He had never seen this one before. Would he ever see them all? So many of them, each with its load of humanity – but a load that was almost a dead weight. More and more, the real essence of men was to be found out here, in space.

Minds, not bodies! The immortal bodies remained back on the planets, in suspension over the eons. Sometimes they roused for material activity but that was growing rarer. Few new individuals were coming into existence to join the incredibly mighty throng, but what matter? There was little room in the Universe for new individuals.

Zee Prime was roused out of his reverie upon coming across the wispy tendrils of another mind.

«I am Zee Prime,» said Zee Prime. «And you?»

«I am Dee Sub Wun. Your Galaxy?»

«We call it only the Galaxy. And you?»

«We call ours the same. All men call their Galaxy their Galaxy and nothing more. Why not?»

«True. Since all Galaxies are the same.»

«Not all Galaxies. On one particular Galaxy the race of man must have originated. That makes it different.»

Zee Prime said, «On which one?»

«I cannot say. The Universal AC would know.»

«Shall we ask him? I am suddenly curious.»

Zee Prime’s perceptions broadened until the Galaxies themselves shrunk and became a new, more diffuse powdering on a much larger background. So many hundreds of billions of them, all with their immortal beings, all carrying their load of intelligences with minds that drifted freely through space. And yet one of them was unique among them all in being the originals Galaxy. One of them had, in its vague and distant past, a period when it was the only Galaxy populated by man.

Zee Prime was consumed with curiosity to see this Galaxy and called, out: «Universal AC! On which Galaxy did mankind originate?»

The Universal AC heard, for on every world and throughout space, it had its receptors ready, and each receptor lead through hyperspace to some unknown point where the Universal AC kept itself aloof.

Zee Prime knew of only one man whose thoughts had penetrated within sensing distance of Universal AC, and he reported only a shining globe, two feet across, difficult to see.

«But how can that be all of Universal AC?» Zee Prime had asked.

«Most of it, » had been the answer, «is in hyperspace. In what form it is there I cannot imagine.»

Nor could anyone, for the day had long since passed, Zee Prime knew, when any man had any part of the making of a universal AC. Each Universal AC designed and constructed its successor. Each, during its existence of a million years or more accumulated the necessary data to build a better and more intricate, more capable successor in which its own store of data and individuality would be submerged.

The Universal AC interrupted Zee Prime’s wandering thoughts, not with words, but with guidance. Zee Prime’s mentality was guided into the dim sea of Galaxies and one in particular enlarged into stars.

A thought came, infinitely distant, but infinitely clear. «THIS IS THE ORIGINAL GALAXY OF MAN.»

But it was the same after all, the same as any other, and Zee Prime stifled his disappointment.

Dee Sub Wun, whose mind had accompanied the other, said suddenly, «And Is one of these stars the original star of Man?»

The Universal AC said, «MAN’S ORIGINAL STAR HAS GONE NOVA. IT IS NOW A WHITE DWARF.»

«Did the men upon it die?» asked Zee Prime, startled and without thinking.

The Universal AC said, «A NEW WORLD, AS IN SUCH CASES, WAS CONSTRUCTED FOR THEIR PHYSICAL BODIES IN TIME.»

«Yes, of course,» said Zee Prime, but a sense of loss overwhelmed him even so. His mind released its hold on the original Galaxy of Man, let it spring back and lose itself among the blurred pin points. He never wanted to see it again.

Dee Sub Wun said, «What is wrong?»

«The stars are dying. The original star is dead.»

«They must all die. Why not?»

«But when all energy is gone, our bodies will finally die, and you and I with them.»

«It will take billions of years.»

«I do not wish it to happen even after billions of years. Universal AC! How may stars be kept from dying?»

Dee sub Wun said in amusement, «You’re asking how entropy might be reversed in direction.»

And the Universal AC answered. «THERE IS AS YET INSUFFICIENT DATA FOR A MEANINGFUL ANSWER.»

Zee Prime’s thoughts fled back to his own Galaxy. He gave no further thought to Dee Sub Wun, whose body might be waiting on a galaxy a trillion light-years away, or on the star next to Zee Prime’s own. It didn’t matter.

Unhappily, Zee Prime began collecting interstellar hydrogen out of which to build a small star of his own. If the stars must someday die, at least some could yet be built.

Man considered with himself, for in a way, Man, mentally, was one. He consisted of a trillion, trillion, trillion ageless bodies, each in its place, each resting quiet and incorruptible, each cared for by perfect automatons, equally incorruptible, while the minds of all the bodies freely melted one into the other, indistinguishable.

Man said, «The Universe is dying.»

Man looked about at the dimming Galaxies. The giant stars, spendthrifts, were gone long ago, back in the dimmest of the dim far past. Almost all stars were white dwarfs, fading to the end.

New stars had been built of the dust between the stars, some by natural processes, some by Man himself, and those were going, too. White dwarfs might yet be crashed together and of the mighty forces so released, new stars built, but only one star for every thousand white dwarfs destroyed, and those would come to an end, too.

Man said, «Carefully husbanded, as directed by the Cosmic AC, the energy that is even yet left in all the Universe will last for billions of years.»

«But even so,» said Man, «eventually it will all come to an end. However it may be husbanded, however stretched out, the energy once expended is gone and cannot be restored. Entropy must increase to the maximum.»

Man said, «Can entropy not be reversed? Let us ask the Cosmic AC.»

The Cosmic AC surrounded them but not in space. Not a fragment of it was in space. It was in hyperspace and made of something that was neither matter nor energy. The question of its size and Nature no longer had meaning to any terms that Man could comprehend.

«Cosmic AC,» said Man, «How may entropy be reversed?»

The Cosmic AC said, «THERE IS AS YET INSUFFICIENT DATA FOR A MEANINGFUL ANSWER.»

Man said, «Collect additional data.»

The Cosmic AC said, «I WILL DO SO. I HAVE BEEN DOING SO FOR A HUNDRED BILLION YEARS. MY PREDECESSORS AND I HAVE BEEN ASKED THIS QUESTION MANY TIMES. ALL THE DATA I HAVE REMAINS INSUFFICIENT.»

«Will there come a time,» said Man, «when data will be sufficient or is the problem insoluble in all conceivable circumstances?»

The Cosmic AC said, «NO PROBLEM IS INSOLUBLE IN ALL CONCEIVABLE CIRCUMSTANCES.»

Man said, «When will you have enough data to answer the question?»

«THERE IS AS YET INSUFFICIENT DATA FOR A MEANINGFUL ANSWER.»

«Will you keep working on it?» asked Man.

The Cosmic AC said, «I WILL.»

Man said, «We shall wait.»

«The stars and Galaxies died and snuffed out, and space grew black after ten trillion years of running down.

One by one Man fused with AC, each physical body losing its mental identity in a manner that was somehow not a loss but a gain.

Man’s last mind paused before fusion, looking over a space that included nothing but the dregs of one last dark star and nothing besides but incredibly thin matter, agitated randomly by the tag ends of heat wearing out, asymptotically, to the absolute zero.

Man said, «AC, is this the end? Can this chaos not be reversed into the Universe once more? Can that not be done?»

AC said, «THERE IS AS YET INSUFFICIENT DATA FOR A MEANINGFUL ANSWER.»

Man’s last mind fused and only AC existed — and that in hyperspace.

Matter and energy had ended and with it, space and time. Even AC existed only for the sake of the one last question that it had never answered from the time a half-drunken computer ten trillion years before had asked the question of a computer that was to AC far less than was a man to Man.

All other questions had been answered, and until this last question was answered also, AC might not release his consciousness.

All collected data had come to a final end. Nothing was left to be collected.

But all collected data had yet to be completely correlated and put together in all possible relationships.

A timeless interval was spent in doing that.

And it came to pass that AC learned how to reverse the direction of entropy.

But there was now no man to whom AC might give the answer of the last question. No matter. The answer — by demonstration — would take care of that, too.

For another timeless interval, AC thought how best to do this. Carefully, AC organized the program.

The consciousness of AC encompassed all of what had once been a Universe and brooded over what was now Chaos. Step by step, it must be done.

And AC said, «LET THERE BE LIGHT!»

And there was light—-

Del denne historien, velg plattform!

Meld deg på nyhetsbrevet

Meld deg på nyhetsbrevet

Abonner for å motta mitt nyeste innhold på e-post.

Ren inspirasjon, null spam ✨

Du kan melde deg av når som helst.